Superbugs Explained: The Growing Crisis of Antibiotic Resistance

Superbugs: Understanding the Rising Threat

Antibiotic resistance is not a future concern. It’s a present and growing crisis, quietly reshaping how we treat infections. Superbug bacteria that no longer respond to standard antibiotics pose the highest risk to older adults.

These infections can begin with minor wounds, urinary tract infections, or post-surgery complications. But when resistant bacteria take hold, routine treatment fails. This forces doctors to use more potent, riskier drugs or, in some cases, no drugs at all.

Antibiotic-resistant infections can delay surgeries, complicate recovery, and increase the need for long-term care. Seniors in hospitals or care facilities are at a higher risk of exposure to these threats. Yet this issue rarely appears in conversations about aging or end-of-life planning.

People who donate their bodies to science also play a role here. Studying antibiotic resistance in donated tissues helps researchers understand how resistance behaves in aging immune systems. Few realize how body donation contributes to the fight against superbugs.

What Are Superbugs?

Superbugs are bacteria that have developed resistance to antibiotics, meaning bacteria no longer die when exposed to them. They adapt, survive, and spread, especially in healthcare settings. These aren’t rare organisms they can live on bedrails, catheters, or even hands.

Superbugs don’t just resist treatment. They force more extended hospital stays, increase pain, and limit end-of-life care options. For older adults, even a minor infection from a superbug can quickly become life-threatening.

Doctors sometimes have to turn to experimental or toxic drugs when superbugs strike. These medications carry greater risks, especially for older individuals with weakened immune systems. Most families don’t learn about this until it’s too late.

How Superbugs Form

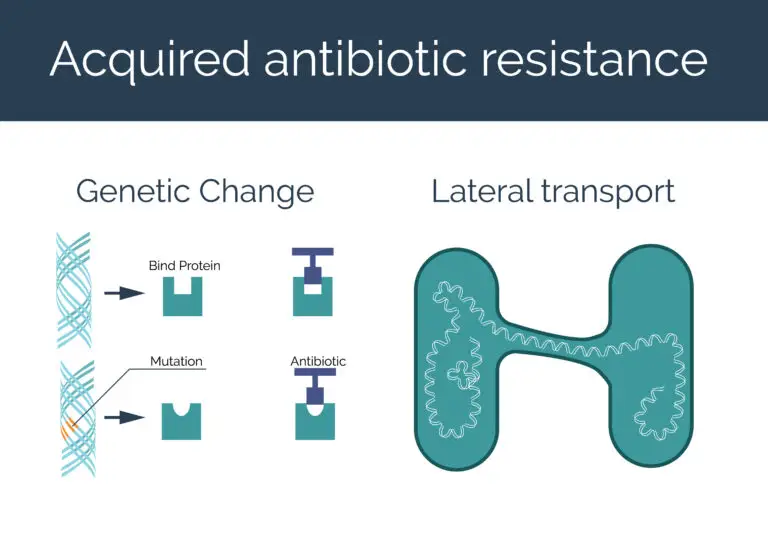

Superbugs form when bacteria survive repeated exposure to antibiotics. Each time an antibiotic fails to kill a microbe, it gives that microbe a chance to adapt. Over time, those survivors multiply and pass on their resistance.

What is often overlooked is how this process unfolds within real people. For example, when an older adult fails to complete an antibiotic course, even for a mild infection, resistant strains may develop within their body. These strains can later infect others or lie dormant until the person becomes more vulnerable.

In care facilities, resistant bacteria pass easily between residents through shared staff, equipment, or surfaces. This silent evolution of bacteria often begins in small, preventable ways.

Examples of Common Superbugs

Some superbugs now thrive in environments where people expect safety, such as hospitals, nursing homes, and even home care settings. MRSA (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) often enters through skin wounds or surgical sites. It spreads on hands, sheets, and even blood pressure cuffs.

CRE (Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae) thrives in the gut and bloodstream. It resists nearly all antibiotics, including last-resort drugs. Seniors with feeding tubes or catheters face a higher risk of infection.

VRE (Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci) targets individuals with weakened immune systems. It resides in the intestines but can travel to the bloodstream or the heart.

These bacteria don’t just resist treatment they adapt to their environment. Superbugs exploit weakened bodies, crowded care environments, and outdated infection control practices. They’re not future threats. They are here, now, and already inside some care facilities.

How Antibiotic Resistance Develops

Antibiotic resistance builds silently inside the body. It starts when antibiotics target not only the harmful bacteria but also the helpful ones. Over time, the strongest survive.

Older adults take more antibiotics than any other age group. Many receive them as a precaution, rather than as a treatment. This routine use can wipe out protective bacteria, leaving room for superbugs to grow.

Bacteria share resistance genes through plasmids, tiny loops of DNA passed between species. This means a harmless gut bacterium can give resistance to a deadly one. These microscopic exchanges happen during hospital stays, in rehab centers, or even at home during recovery.

This hidden evolution leaves fewer options for care when someone truly needs help.

The Science Behind Resistance

Bacteria survive by changing fast. Some develop resistance through random mutations. Others borrow resistance genes from different bacteria in the body. This sharing happens silently, often before symptoms appear.

In aging bodies, where immune defenses slow down, bacteria face less pressure. That gives them time to adapt and spread. Antibiotics taken years ago may still shape the bacteria living inside a person today.

Biofilms make things worse. These slimy layers form on medical devices, such as catheters and joint replacements. Inside biofilms, bacteria communicate and swap resistance traits. Once resistance takes hold in a biofilm, removing it often means surgery, not just more potent drugs.

Most people never hear this. But it changes everything about how we approach care in later life.

Human and Agricultural Antibiotic Use

Antibiotics don’t just come from prescriptions. They enter the body through food, water, and even air. Many farms administer antibiotics to healthy animals, not to treat illness, but to accelerate growth. Overuse creates resistant bacteria in animals, which can spread to humans through contaminated meat, soil, and wastewater.

Older adults with weakened immunity may be at risk of exposure through unwashed produce, undercooked meats, or frequent hospital meals. Few people realize how often resistance begins outside the clinic.

Even drinking water can carry traces of antibiotics or resistant bacteria from agricultural runoff. These low doses don’t kill bacteria they teach them how to survive.

Resistance isn’t just a medical issue. It’s environmental, nutritional, and deeply connected to how society manages life and death.

Global Threat of Superbugs: A Health Crisis in Motion

Superbugs do not stay local. They travel with people, medical equipment, and even funeral preparations. Resistant bacteria found in one hospital can appear in another country within days.

For older adults, the risks multiply. Hospital visits, assisted living stays, and rehab centers increase exposure. Each new care setting means new bacteria. Many of them already resist treatment.

Antibiotic resistance doesn’t just affect the sick. It disrupts routine care, such as joint replacements, dialysis, or wound healing. These services rely on infection control, which is now undermined by resistance.

International Spread and Hospital Burdens

Superbugs cross borders faster than most diseases. Medical tourism, global travel, and the transfer of patients carry resistant bacteria from one facility to another. Even the most advanced hospitals struggle when antibiotics fail.

Long-term care centers feel the heaviest burden. Many operate with limited staff, shared rooms, and high antibiotic use. That creates a perfect breeding ground for resistance.

Some hospitals now screen patients for superbugs at admission. Others isolate infected individuals. These steps slow the spread but add strain on already overwhelmed systems.

Older adults often transition through multiple facilities, including hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and home care. Each transfer risks exposure to new resistant strains. These bacteria follow people, not just places. And they leave fewer treatment options with every move.

Can Antibiotic Resistance Be Prevented or Reversed?

Antibiotic resistance cannot be entirely reversed once it has spread within a population. But its growth can slow. Resistance begins at the individual level, not just through policies or prescriptions.

Older adults can make a difference by asking hard questions about antibiotics. Do I need this drug? What happens if I wait? When patients and caregivers understand the risks, they help stop unnecessary use.

Care decisions near the end of life often include antibiotics by default. Many families choose them to ease worry, not always based on need. These moments matter. One prescription given without cause can strengthen resistance across a community.

Is Antibiotic Resistance Reversible?

Once a bacterial strain becomes resistant, it rarely becomes susceptible again. The genes that allow survival stay active, even if antibiotics are removed. That resistance can lie dormant in the body or on surfaces, waiting for the next vulnerable host.

Older adults often carry these bacteria without symptoms. During surgery, catheter use, or immune decline, resistance becomes active. This delay between exposure and illness makes it hard to trace or reverse.

Even if one drug stops being used, bacteria may keep their resistance in case they reencounter it. It’s a form of microbial memory, one that complicates future care.

Preventing Antibiotic-Resistant Infections

Preventing antibiotic-resistant infections starts with small, daily choices. Handwashing, wound care, and maintaining clean living spaces reduce the likelihood of bacteria entering the body. For older adults, even a minor cut, such as a paper cut, can become dangerous if exposed to resistant microbes.

Vaccinations matter too. They reduce the need for antibiotics in the first place. Fewer infections mean fewer prescriptions. And fewer prescriptions mean fewer chances for resistance to grow.

Medical staff must follow strict hygiene protocols, but families play a role as well. Visitors should sanitize their hands before touching loved ones. Caregivers must speak up when antibiotics are offered without a clear need.

How Antibiotic Resistance Spreads

Antibiotic resistance spreads without warning. It moves through unwashed hands, shared medical tools, and surfaces that no one thinks to clean, such as elevator buttons or walkers.

In older adults, a person may carry resistant bacteria without symptoms. But once hospitalized or weakened, those same bacteria can trigger serious infection.

Resistance also travels through families. A caregiver unknowingly carries bacteria from a hospital room to their own kitchen. Pets, food, and visitors become part of the chain.

In Hospitals and Care Facilities

Hospitals and long-term care facilities create ideal conditions for the growth of resistant bacteria. Patients receive repeated antibiotics, many have open wounds, and staff move quickly between rooms. Even well-meaning care can spread infection.

Older adults often share bathrooms, blood pressure cuffs, and bedrails. These everyday items collect bacteria over time. Cleaning protocols are helpful, but some microbes can survive even bleach.

Some residents never show symptoms. They carry resistant bacteria in their skin, guts, or nose. One shared towel or meal tray can be passed to others.

In care homes, it rarely appears in discharge paperwork, but it remains with the person and sometimes enters the next facility undetected. This hidden transfer threatens recovery and end-of-life care.

Community and Food Sources

Antibiotic resistance doesn’t stay in hospitals. It spreads through grocery stores, kitchens, and public restrooms. Bacteria from farms, animals, or sewage can survive on fresh produce or undercooked meat. Once eaten, they may colonize the gut without symptoms.

Older adults with low stomach acid or weak digestion face a greater risk. These bacteria can cross into the bloodstream during illness or surgery. They don’t need to cause immediate infection to become a long-term threat.

Even the soil in a garden or the dust in a home can carry resistant strains. Families that handle raw meat, clean up after pets, or prepare food for the elderly play an unrecognized role in either stopping or spreading resistance.

Can Antibiotic Resistance Cause Death?

Antibiotic resistance can turn treatable infections into fatal ones. When standard drugs fail, infections spread faster than the body can respond. Older adults face the highest risk.

A simple UTI or chest infection can escalate to sepsis in days. Once sepsis sets in, organs begin to shut down rapidly. Even aggressive treatment may not be able to reverse the damage.

End-of-life decisions become more complicated. Families must weigh whether to use toxic last resort antibiotics or shift to comfort care. In many cases, there’s no time to choose. The infection outruns the conversation.

Resistant infections now kill more people than some cancers. Yet most people don’t know the risk until they face it.

Mortality Statistics

In 2019, antibiotic-resistant infections directly caused 1.27 million deaths and contributed to nearly 4.95 million deaths according to the World Health Organization. These figures place antibiotic resistance ahead of HIV/AIDS or malaria in global mortality. Older adults carried a high burden, especially those undergoing routine procedures like catheter placement or minor surgery, where infections became untreatable.

In long-term care and hospice, superbugs such as MRSA and CRE often silently drive fatal outcomes described simply as “complications.” Families rarely learn that drug-resistant bacteria were at fault.

Which Antibiotics Cause Resistance?

All antibiotics can contribute to the development of resistance if misused. But broad-spectrum drugs like fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins carry the highest risk. These drugs target multiple types of bacteria simultaneously, including beneficial ones that protect the body.

Older adults often receive these antibiotics during hospital stays, even when tests haven’t confirmed infection. They may get started “just in case,” especially after falls, surgeries, or fevers. This overuse clears the way for resistant bacteria to grow and spread.

Repeated courses over a lifetime also matter. A person who has taken antibiotics for decades may unknowingly carry resistant strains in their gut, mouth, or skin. These bacteria can become active when immunity is weakened.

The Role of Misuse in Resistance

Misuse of antibiotics doesn’t always look reckless. Sometimes it starts with good intentions—a caregiver pushing for quick relief, or a doctor prescribing out of caution. But each unnecessary dose teaches bacteria how to survive.

Older adults often receive antibiotics for viral illnesses, where the drugs have no effect. Other times, they stop treatment early because the side effects feel worse than the illness. Both actions give bacteria time to adapt.

Misuse also occurs when antibiotics are administered without prior culture tests. Treating the wrong bug with the incorrect medication accelerates resistance. It kills off vulnerable bacteria while leaving the resistant ones behind.

Classes of High-Risk Antibiotics

Some antibiotics carry a higher risk of fueling resistance. Fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and carbapenems top that list. They kill a wide range of bacteria, which sounds helpful, but that power comes with a cost.

These drugs don’t just wipe out the infection. They erase protective bacteria that live in the gut, mouth, and skin. That leaves room for dangerous strains to take over, especially in older adults with weaker immune defenses.

Many hospitals use these antibiotics as first-line treatments, even when simpler options may be more effective. Over time, bacteria exposed to these drugs become increasingly resistant to being killed. That forces doctors to rely on last-resort treatments that can harm kidneys, hearing, or cognition

Slowing the Crisis: What Can Be Done

Slowing antibiotic resistance doesn’t require new science it starts with how people use the tools we already have. Seniors, caregivers, and families hold real power. Every decision to pause, question, or refuse unnecessary antibiotics protects future treatment options.

Simple actions matter. Hand hygiene, wound care, and vaccine updates can prevent infections from ever starting. Asking whether an antibiotic is truly needed shifts the culture of overprescribing.

In healthcare systems, doctors and nurses need support to say “no” when antibiotics won’t help. Pressure from families or fear of being sued sometimes leads to prescriptions that do more harm than good.

Global Action and Research Efforts

Around the world, researchers track superbugs like storm systems. They study hospital outbreaks, test wastewater, and monitor livestock for the presence of resistant strains. But real progress comes when countries share data and commit to fewer unnecessary prescriptions.

Global programs now focus on developing narrow-spectrum antibiotics that target only the bacteria causing harm. These reduce collateral damage to the body’s natural defenses. However, progress moves slowly, and drug companies often avoid this type of research. The return on investment doesn’t match the urgency of the problem.

Some of the most valuable work happens with donated bodies. Researchers study how resistant bacteria behave in real human tissue, especially in older adults. That research guides safer treatments and helps others live longer, healthier lives.

What Older Adults and Caregivers Can Do

Older adults and their caregivers play a significant role in shaping how antibiotic resistance develops or is slowed. Their choices carry weight, especially in the final years of life when antibiotics are often given automatically.

Start by asking questions. Is this infection bacterial or viral? Can we wait for test results? What are the risks of not using antibiotics right now?

Caregivers play a vital yet often overlooked role. They manage hygiene, prevent pressure sores, and notice early signs of infection. Clean hands, well-cared-for wounds, and a balanced diet can help prevent the need for antibiotics in the first place.

Facing the Challenge of Superbugs Together

Antibiotic resistance is being recognized as a growing concern in both healthcare and community settings. Its spread is often unintentional, shaped by habits, routine care, and a lack of information about the long-term impact of certain decisions.

When antibiotics are used with care and supported by hygiene and prevention efforts, resistance can be slowed. These small actions, such as frequent hand washing, completing prescribed treatments, and reducing unnecessary medications, have been shown to make a significant difference.

Progress is being made through research, education, and collaboration. With continued awareness and thoughtful choices, the reach of superbugs can be limited, and existing treatments can be preserved for those who genuinely need them.